The Flynn effect is the long-term rise in average IQ test scores, roughly three points per decade through the 20th century. It has slowed and, in several developed countries since the 1990s, partially reversed, although meta-analyses still find overall gains continuing worldwide. Recent within-family studies indicate these shifts are driven by environmental factors, not genetics or immigration.

What is the Flynn effect?

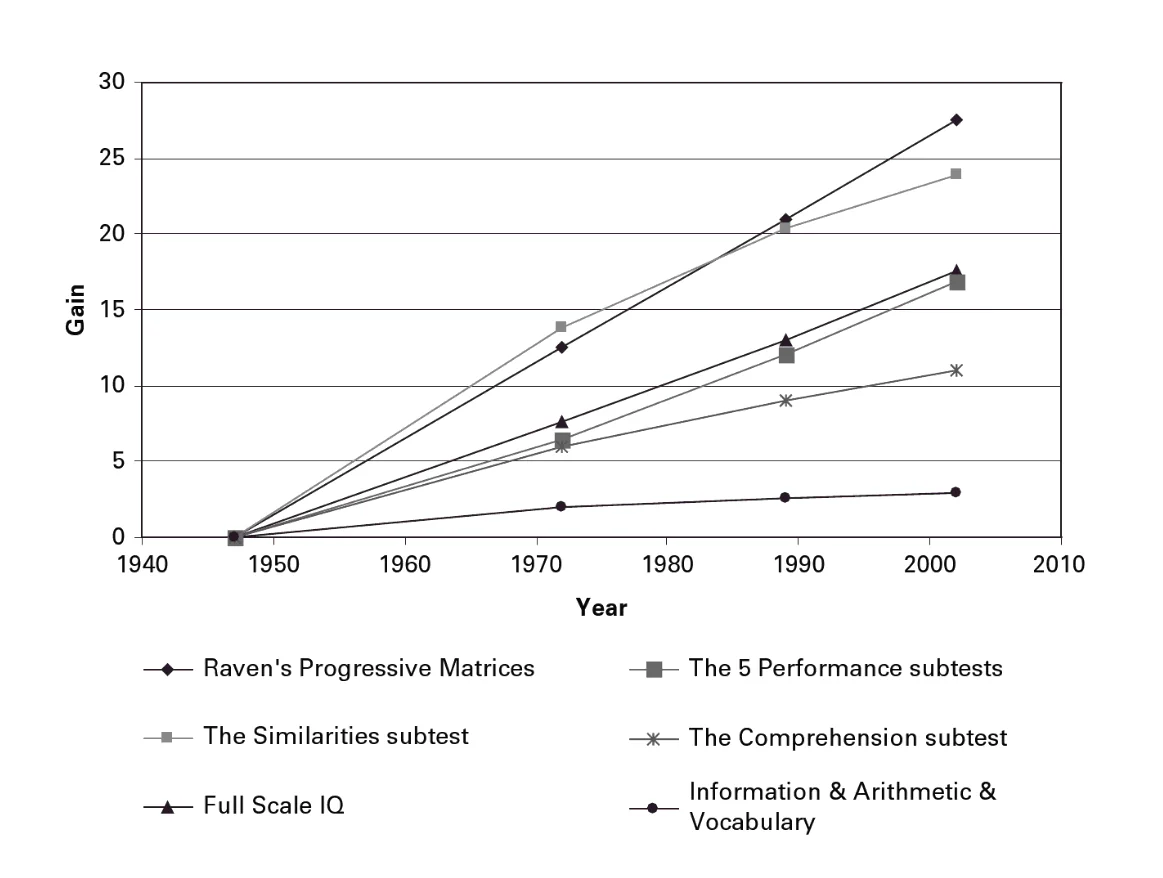

The Flynn effect is the observed increase over time in population performance on standardized intelligence tests. When IQ tests are revised, publishers re-norm them so the average is 100, but raw performance on older forms rises across cohorts. For example, British children gained about 14 points on Raven’s Progressive Matrices from the 1940s to the 2000s (overview).

Population IQ performance rose by about 2–3 points per decade across much of the 20th century, with larger gains on problem-solving and spatial reasoning than on vocabulary.

Because tests are periodically re-normed, the average reported IQ remains 100. The effect is detected by comparing how newer cohorts score on older test forms, by tracking military or school test batteries that report raw scores, or by comparing successive norms. This is why it is accurate to say scores increased even though “IQ is always 100” after normalization, a point sometimes called IQ normalization.

How does the Flynn effect work?

No single cause explains the trend. Evidence points to multiple environmental drivers that especially boost skills tapped by modern tests, such as abstract, visual, and logical reasoning. Research frequently cites:

- Education and IQ: Longer and more effective schooling raises test performance. A meta-analysis found each additional year of formal education increases IQ by roughly 1 to 5 points (summary).

- Test familiarity and cognitive demands: Greater exposure to tests and to cognitively complex work and media can improve abstract problem solving (overview).

- Nutrition and health: Better early-life nutrition, including iodine sufficiency, is linked to higher cognitive performance. Iodization and reduced infectious disease burdens are associated with gains in test scores (sources summarized).

- Reduced toxins: Lower lead exposure correlates with population IQ increases; U.S. blood lead declines from the 1970s to 2000s are linked with 4–5 point IQ gains (Kaufman et al., 2014).

Gains tend to be largest on fluid-reasoning measures like Raven’s Progressive Matrices, supporting the idea that changing environments build abstract problem-solving skills.

Is the Flynn effect reversing?

In some countries, yes. Norway shows a clear rise, a mid-1970s peak, then a decline through the late 1980s among male conscripts. Crucially, a within-family analysis recovered the same pattern, ruling out population-composition explanations and pointing to environmental causes within families (Bratsberg & Rogeberg, 2018). Denmark reported a similar slowdown then decline in conscript scores, Australia saw a stall in younger children, and the U.K. recorded drops among older teens (country data).

At the same time, broad reviews through the mid-2010s still found an overall positive trend worldwide, though often smaller in developed nations (Pietschnig & Voracek, 2015), (Trahan et al., 2014). Newer psychometric work suggests the modern rate can be lower than the historical ~3 points per decade. For example, a comparison using WAIS-5 validity data inferred about 1.2 points per decade and discussed recent influences like social media dependency and pandemic disruption as potential contributors (Winter et al., 2024).

Overall, the best-supported conclusion is mixed: gains have slowed, some places and subtests show plateaus or declines, and the direction can change over time. Where declines are observed, they are likely environmental.

Do immigration or genetics explain recent declines?

Current evidence says no. The Norwegian within-family study found the rise, peak, and decline all occur among siblings in the same families, which rules out explanations based on immigration or broad genetic change and instead implicates environmental shifts that vary within families over time (PNAS 2018). The magnitude and speed of recent declines are also too large to be plausibly genetic. While genetic selection against education-linked alleles has been estimated at a fraction of a point per decade in some datasets, that effect is small compared with observed environmental swings.

How can IQ go up if the average is always 100?

IQ tests are periodically re-normed so that the average score of the current standardization sample is 100 with a fixed spread. The Flynn effect is detected by comparing how newer cohorts perform on older norms or on raw-score reporting batteries. Higher raw scores over time, even after age-adjustment, mean people are answering more items correctly than earlier cohorts, which is the essence of the effect. This process is called IQ normalization, and it is why “average 100” can coexist with rising or falling underlying performance.

What are the limitations and what does this mean?

IQ tests measure a set of cognitive skills, not intelligence in every sense. Changes can differ by domain, for example some reports of a reverse Flynn effect are strongest on spatial subtests, and cultural shifts or outdated items can affect specific measures (Gonthier et al., 2021). Cross-country comparisons also vary in test type, sampling, and policy context.

Implications are practical rather than alarmist. Environmental levers that boosted scores in the past still matter: reduce toxins like lead, ensure adequate early-life nutrition, maintain infectious-disease control, and invest in effective, rigorous schooling. As learning environments evolve, researchers are now testing how factors like screen-mediated study, shorter attention windows, and pandemic-era schooling disruptions relate to performance trends (Winter et al., 2024). The evidence to date supports focusing on modifiable environments rather than immutable traits.