The single strontium atom photo is real. It shows a single, laser-cooled Sr+ ion held between electrodes in an ion trap and made to glow by laser-induced fluorescence, which a standard camera can record in a long exposure. You are seeing light scattered by that atom, not a resolved image of its physical size or structure.

What is the single strontium atom photo?

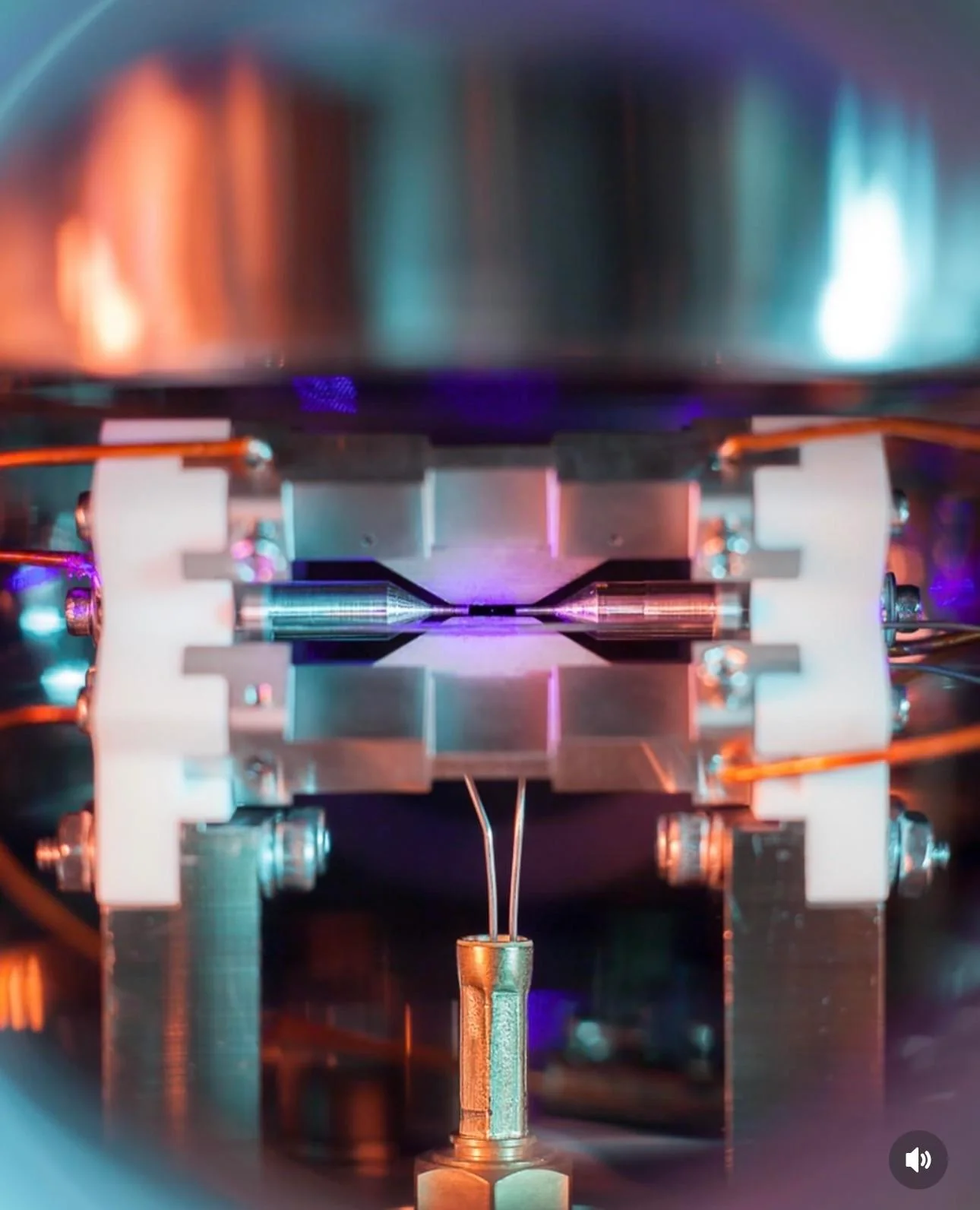

The image, titled “Single Atom in an Ion Trap,” was captured by physicist David Nadlinger at the University of Oxford and won the UK’s EPSRC Science Photography Competition in 2018. The bright purple dot in the center is a single positively charged strontium ion (Sr+) fluorescing as lasers drive one of its electronic transitions while it is suspended between metal electrodes in a high vacuum. Major outlets validated and explained the image at the time, including the BBC and The New York Times (BBC report; NYT coverage).

In the award-winning photo, the two needle-like electrodes are roughly a couple of millimeters apart; the glowing dot between them is one atom scattering photons into the camera.

How can you see a single atom without a microscope?

A single atom is far too small to resolve directly with visible light. The trick is to make the atom act like a tiny light source. When a tuned laser shines on a suitable electronic transition of an atom or ion, the atom repeatedly absorbs and re-emits photons. This laser-induced fluorescence produces a steady stream of visible light that a camera can collect over a long exposure.

Laser-induced fluorescence is the detection of atoms by the visible light they re-emit after being excited by a laser, often yielding millions of photons per second from a single trapped ion.

Because the camera integrates many photons over seconds, the atom appears as a bright point. There is no need for a microscope objective in this setup because the atom is held in free space between relatively large electrodes and emits enough light for a standard DSLR to register it, as noted in contemporary news coverage (BBC).

How does the ion trap and laser cooling work?

The atom in the image is not floating freely. It is a charged atom, or ion, confined by a device called a Paul trap (ion trap) that uses oscillating electric fields to create a stable, three-dimensional potential well. Inside ultra-high vacuum, the ion is isolated from collisions with background gas.

To keep the ion nearly motionless, researchers use laser cooling, tuning laser light slightly below a strong electronic transition. The ion preferentially absorbs photons when it moves toward the laser, losing kinetic energy overall. In strontium ions, a blue-violet transition near 422 nanometers is commonly used for cooling and fluorescence, with additional “repump” lasers to keep the atom cycling. These are standard techniques in trapped-ion quantum computing and precision measurement.

What does the image show, and what doesn’t it show?

- It shows fluorescence, not size. The purple speck is a diffraction-limited spot formed by the camera optics. It does not represent the atom’s physical diameter, which is about 0.2–0.3 nanometers and impossible to resolve with visible light.

- The scale is macroscopic. The electrodes you see are spaced on the order of millimeters, and the screws in the apparatus are ordinary hardware sizes. The single glowing point sits midway between the electrode tips (BBC).

- It is not a glow from an electric field alone. The light is produced by the atom itself, absorbing and re-emitting laser photons. The trap’s fields hold the ion but do not make it visibly glow.

- Long exposure makes it visible. A DSLR integrating many photons over seconds can render one atom bright against a dark background.

Why strontium, and why does it matter?

Strontium ions have convenient, strong optical transitions in the visible spectrum, making them easy to laser-cool and detect with fluorescence. They also have stable isotopes and well-characterized energy levels, which is why Sr+ is a workhorse in ion-trap labs. The same methods behind the photo underpin two major technologies:

- Trapped-ion quantum computing. Individual ions serve as qubits, manipulated and read out via lasers and fluorescence detection (overview).

- Optical atomic clocks. Strontium-based clocks, using either trapped ions or neutral atoms in optical lattices, are among the most accurate timekeepers known (optical clock).

The photo is a public-friendly glimpse of laboratory techniques that define today’s most precise measurements and quantum information experiments.

How big is it, really?

Even under ideal conditions, a visible-light camera cannot resolve features smaller than roughly a few hundred nanometers due to diffraction. An atom is about a million times smaller than a millimeter, so it will always appear as a point-like spot in such images. The “size” of the dot you see is set by the camera lens and sensor, not by the atom’s actual extent.

Bottom line

Yes, the single strontium atom photo is authentic. It captures the visible fluorescence from a lone, laser-cooled Sr+ ion held in an ion trap, recorded by a standard camera in a long exposure. It does not show the atom’s shape, but it does let you see light from a single atom with the naked eye through a camera viewfinder, which is precisely why the image is remarkable.