The Enigma Eins Catalogue was a precomputed lookup list of how the plaintext word eins would encrypt under every relevant Enigma configuration and message position. Codebreakers used it to scan intercepted ciphertext for four-letter sequences that could be “eins,” then built rapid bombe runs from those hits to recover the day’s Enigma key. It turned a frequent German plaintext fragment into a systematic starting point for decryption.

What is the Enigma Eins Catalogue?

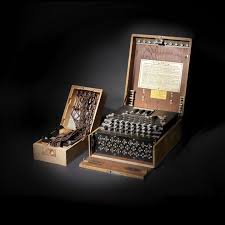

The Enigma Eins Catalogue was a crib catalogue compiled at Bletchley Park. A crib is a guessed fragment of plaintext that likely appears somewhere in a cipher. Because German operators often spelled out numbers in messages, the word “eins” (one) appeared frequently. Analysts prepared a catalogue listing the ciphertext outcomes that “eins” could produce for every considered rotor order, ring setting, and relative position of the Enigma rotors. This let them check intercepted traffic quickly for matches.

Cribs like “eins” gave the bombes something concrete to test. A short, likely plaintext string anchors a much larger search for rotor settings and plugboard wiring.

How did the Eins Catalogue work?

The Enigma machine applied a position-dependent substitution with three or four rotors, a reflector, and a configurable plugboard. Each keystroke stepped the rotors, so the same letter encrypted differently at different positions. For a specific daily key, the internal wiring and ring settings were fixed, but each message had its own starting position. The Eins Catalogue tabulated, for each rotor order and start position, what the four-letter plaintext E I N S would look like after passing through the machine’s rotor stack. Operators then slid a four-letter window across intercepted ciphertext to look for those patterns.

A plausible match did not finish the job. It yielded a promising rotor position and order to construct a menu for the Enigma bombe, the electromechanical device that searched plugboard pairings and starting positions. Bombe runs built from short cribs were fast to set up, and hits produced candidate keys that could be verified by decrypting more of the day’s traffic. See overviews of bombes and menus at the Crypto Museum and Bletchley Park.

Key property: in Enigma, a letter never encrypts to itself, which helps validate or reject crib alignments quickly (technical overview).

Why did “eins” appear often in Enigma messages?

German military procedure commonly spelled out numbers in radiograms and logs. Short words like eins, zwei, and drei appeared in coordinates, bearings, counts, headings, and times. Among these, “eins” was especially useful because it is four letters, making it long enough to form an effective crib but short enough to catalogue comprehensively for many machine states. Other recurring cribs such as WETTER (weather) and formal salutations were also exploited when appropriate. Operational details and padding practices varied, so analysts maintained several crib strategies rather than relying on a single word. For context on padding intended to foil cribbing, see padding in cryptography.

How did codebreakers use the Eins Catalogue with the bombe?

- Find candidate alignments: Compare the intercepted ciphertext against the catalogue’s list of four-letter outputs for “eins” at all positions.

- Build a menu: Use the hypothesized plaintext–ciphertext pairing to create a logical wiring diagram, or menu, for a bombe run. Menus incorporate constraints such as “no letter encrypts to itself” to prune the search.

- Run the bombe: The bombe tests starting positions and plugboard pairings consistent with the menu to find solutions. Background on bombes is available from Crypto Museum and the Bletchley Park Trust.

- Verify and exploit: Candidate keys are checked by decrypting more traffic. A correct daily key unlocks all messages that used that key.

What were the limitations and caveats?

- Plugboard uncertainty: The Enigma plugboard swapped letter pairs before and after the rotors, massively expanding the keyspace. The Eins Catalogue alone could not decode messages. It generated good menus for the bombe to solve the plugboard and starting positions.

- False positives: Four-letter matches occur by chance. Analysts rejected alignments that violated Enigma constraints, then relied on bombe results and plaintext coherence to confirm.

- Operational changes: The Germans changed procedures, introduced new rotors, and sometimes added padding to blunt crib-based attacks. Catalogues and menus had to be updated to reflect current keys and machines (Enigma variants).

- Not the only crib: “Eins” was one helpful crib among many. Weather headers, routine report formats, and operator habits all fed into crib construction, often improving the strength of a menu more than any single word could.

Who developed and used the Eins Catalogue?

The catalogue approach is associated with the Bletchley Park teams that industrialized cribbing and bombe operations during the Second World War, notably the work led by Alan Turing and colleagues in Huts 6 and 8 on Army, Air Force, and Naval Enigma. Turing formalized the use of cribs and menus for bombes, while many analysts and machine operators turned those methods into daily practice. Official histories and museum resources describe how cribs underpinned bombe success at scale (Bletchley Park, Crypto Museum).