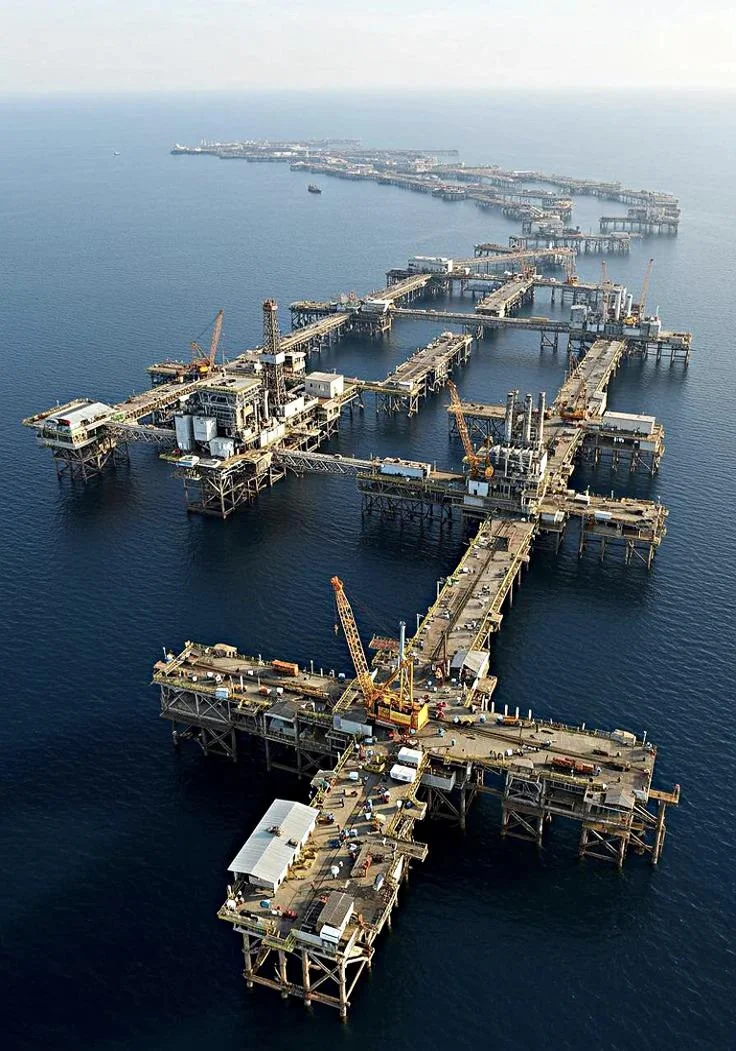

Neft Dashlari, also known as Oil Rocks, is the world’s first offshore oil city, built in 1949 on the Caspian Sea off the coast of Azerbaijan. The settlement consists of hundreds of oil platforms, residential buildings and industrial facilities connected by a web of trestle bridges that once totaled more than 200 kilometers of roads. Today, Neft Dashlari still produces oil and houses around 2,000 rotating workers, even as large parts of this Soviet-era “city above the sea” rust, collapse and sink into the water.

From above, Neft Dashlari looks like a metallic spider sprawled across the waves: old ships scuttled as foundations, apartment blocks perched on stilts, and long causeways stretching into the fog. At its peak, more than 5,000 people lived and worked here, with a theater, bakery, soccer pitch and even a park planted on steel platforms, all more than 30 kilometers from the nearest shoreline.

What is Neft Dashlari (Oil Rocks)?

Neft Dashlari, meaning “Oil Rocks” in Azerbaijani, is an offshore industrial settlement located in the Caspian Sea, about 39 to 40 kilometers from the nearest mainland shore and roughly 60 to 86 kilometers from Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan. It is a fully functioning town built on piles, artificial islands and sunken ships, recognized by Guinness World Records as the world’s first operating offshore oil platform and the first offshore oil city. According to the Azerbaijani state oil company SOCAR and historical accounts, it once comprised nearly 2,000 wells, around 320 production sites and an extensive network of steel trestle bridges forming streets above the sea.

Originally named Chornye Kamni, or “Black Rocks,” the settlement was later renamed Neft Dashlari to emphasize the petroleum that made its existence possible. The “rocks” in its name refer to the oil-stained outcrops that once broke the surface of the Caspian, signaling huge reserves beneath. Over decades, those rocks disappeared under concrete, steel and an industrial maze that some Azerbaijanis call the “eighth wonder of the world.”

Neft Dashlari is often described as a “city above the sea”: an artificial archipelago of platforms, bridges and buildings devoted almost entirely to oil production.

How was Neft Dashlari built on the open sea?

The story of Neft Dashlari begins in the late 1940s, when Soviet geologists completed large-scale surveys of the Caspian shelf between 1945 and 1948 and identified promising offshore deposits. On November 7, 1949, drillers struck oil about 1,100 meters below the seabed, launching a massive state-backed project to create a permanent production base on the water. According to historical summaries compiled by Azerbaijani researchers, the first infrastructure was basic: a drilling rig, a small accommodation house and narrow walkways built out from a tiny reef where the sea depth was only about 20 meters, shallow enough to anchor heavy structures.

To expand beyond that reef, Soviet engineers used an unorthodox foundation: they deliberately scuttled several old ships to the sea floor and built platforms and trestles on top of them. Over time, this strategy produced an artificial archipelago. In 1951, Neft Dashlari shipped its first tanker of oil to shore, and by 1952 systematic construction of steel trestle bridges began, linking platforms into a growing network. Special crane assemblies, pile-driving hammers and barges were designed in Soviet factories specifically for this site, allowing workers to drive steel piles deep into the seabed and bolt on new segments of roadway.

By the late 1950s and 1960s, large-scale construction transformed the outpost into a true offshore city. Historic accounts from Azerbaijan International Magazine and other sources describe nine-story dormitory blocks, hotels, power plants, bakeries, a lemonade workshop, cultural centers and recreational spaces rising above the water. The steel bridges joined these artificial islands into more than 200 kilometers of streets, and later sources estimate the total web of bridges and access roads eventually exceeded 300 kilometers, though much of it has since collapsed or become unusable.

At its height in the 1960s and 1970s, Neft Dashlari covered around 7 hectares of built area, but its trestle bridges stretched for over 200 kilometers across the Caspian Sea.

What was life like in the world’s first offshore oil city?

For many workers, Neft Dashlari functioned as an isolated industrial town, with its own routines and culture shaped by the sea. Contemporary reports and interviews collected by journalists and documentary filmmakers describe a settlement with everything needed for extended offshore shifts: dormitories, a cinema or theater seating hundreds, a bakery, shops, medical facilities, a helicopter pad and sports fields, including a soccer pitch pressed into the narrow space between pipelines and rigs. Trees and soil were brought in from the mainland to create a small park and green spaces, an improbable patch of vegetation suspended over open water.

During the Soviet era, work schedules and population figures reflected the importance of the field. Encyclopedic entries and state publications indicate that, at its peak, Neft Dashlari housed around 5,000 people at a time, many of them living in nine-story hostels directly above production platforms. Some workers recall week-long or multi-week stays followed by time back onshore, a pattern that evolved into the rotation system used today, typically 15 days at sea followed by 15 days at home, according to more recent figures from SOCAR cited by international energy experts.

Despite its isolation, Neft Dashlari was never a utopia. Memoirs and journalistic accounts reference harsh storms, corrosive salt spray and the psychological strain of living among constant noise from pumps and generators. In heavy weather, sections of the bridges could be dangerous, and several accidents are documented, including a 2015 incident where part of the living quarters collapsed into the sea during a storm, leaving workers missing. Yet for many, the city symbolized Soviet technical prowess and provided relatively stable, well-paid employment connected to Azerbaijan’s crucial oil industry.

How much oil has Neft Dashlari produced and why does it matter?

Neft Dashlari played a pivotal role in both Soviet and Azerbaijani energy history. According to Azerbaijani government and industry sources synthesized in academic articles, the field has produced more than 170 million tons of oil over roughly six decades of operation. SOCAR, the state oil company, reported that total output is now approaching 180 million tons over its 75-year lifespan, with a historic peak of about 7.6 million tons in 1967. These figures made Neft Dashlari a major contributor to the Soviet Union’s mid-century oil boom and later to independent Azerbaijan’s domestic supply.

Technically, Neft Dashlari was a milestone: it demonstrated that large-scale offshore oil production was feasible using platforms, bridges and artificial islands anchored in relatively shallow coastal waters. Scholars of energy history often describe it as the “cradle” of offshore oil engineering, predating the massive platforms that would later appear in the North Sea, the Gulf of Mexico and elsewhere. Techniques tested here, from pile-driven trestles to modular living quarters, informed later offshore designs, even as other regions shifted to deeper-water technologies.

Today, however, Neft Dashlari’s contribution to overall output is modest. SOCAR figures suggest the field now produces less than 3,000 tons of oil per day, roughly 1 million tons per year, a small fraction of Azerbaijan’s total production. Most of this oil is supplied to the domestic market rather than exports. Geologists still estimate that around 30 million tons of recoverable reserves remain, but newer and larger fields have overshadowed this aging complex. Its significance now lies as much in its symbolic and historical value as in the volume of oil it pumps.

Over 70-plus years, Neft Dashlari helped pioneer offshore oil extraction and yielded close to 180 million tons of oil, but today it delivers only a minor share of Azerbaijan’s total production.

What environmental and safety challenges does Neft Dashlari face?

Decades of continuous drilling, heavy industry and exposure to stormy, brackish water have left Neft Dashlari in a fragile state. Journalists and human rights advocates who have visited the site describe collapsed bridge sections, rusting structures and platforms slowly being reclaimed by the sea. Environmental groups, including Azerbaijan’s Oil-Workers Rights Protection Organization, have raised concerns for years about oil spills and untreated wastewater being discharged into the Caspian. Although SOCAR states that closed systems are used to handle production fluids and that extensive work has been done in the last two decades to seal old wells and prevent pollution, independent monitoring is difficult in such a remote and restricted industrial zone.

The location of Neft Dashlari magnifies these environmental stakes. The Caspian Sea is the world’s largest enclosed inland body of water, with a delicate ecosystem and important fisheries shared among several countries. Researchers have documented that the Caspian is already under pressure from multiple stressors, including climate change, fluctuating water levels and pollution from oil and gas operations along its coasts. Aging infrastructure at Neft Dashlari, if not carefully managed and eventually decommissioned, risks adding further contamination through leaking wells, corroded pipelines and accidental spills.

Worker safety is another concern. The combination of old steel trestles, high winds and heavy industrial equipment has led to documented accidents, such as the 2015 collapse of part of the residential block during a severe storm. As some bridges have fallen into the sea and others are no longer maintained, only a fraction of the original road network is still usable. One detailed survey from the late 2000s estimated that of roughly 300 kilometers of roads and bridges, only about 45 kilometers remained in serviceable condition, highlighting the extent of structural decay across the complex.

What is the future of Neft Dashlari?

The long-term fate of Neft Dashlari is uncertain, and it sits at the intersection of energy policy, environmental responsibility and historical preservation. On one hand, SOCAR continues to operate the field and describes it as an “active asset with a unique role” for Azerbaijan, suggesting that production will continue as long as it remains technically and economically viable. Geologists’ estimates of remaining reserves, around 30 million tons, support ongoing extraction for at least some years to come, especially as the field still supplies part of the domestic market.

On the other hand, experts and observers increasingly ask what should happen when the oil finally runs out or the infrastructure becomes too unsafe to maintain. Documentary filmmaker Marc Wolfensberger, who spent years negotiating access for his film “Oil Rocks: City Above the Sea,” has outlined three broad possibilities: a costly and complex dismantling and cleanup operation, a partial conversion into a resort or tourism site, or abandonment that could lead to a major ecological hazard. Some energy analysts have suggested Neft Dashlari could be repurposed as a museum or industrial heritage site, preserving a portion of the structure as a monument to early offshore engineering.

Any future plan will likely unfold in the shadow of broader climate and energy transitions. Azerbaijan hosted COP29, the United Nations climate conference, in Baku in November 2024, just dozens of miles from Neft Dashlari, focusing international attention on the tension between fossil fuel dependence and climate goals. In that context, the rusting city above the sea is more than an engineering curiosity. It is a stark, physical reminder of the fossil-fuel era, its ingenuity and its environmental costs, and a test case for how societies handle aging infrastructure in a warming world.