Why two amino acids drew scientists’ attention

Protein restriction extends lifespan in multiple species, but the precise culprits and protectors within protein have been hard to pin down. Tyrosine and its precursor phenylalanine sit at a metabolic crossroads: they feed the synthesis of dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine, influence insulin signaling, and intersect with stress and inflammation pathways. They also differ by sex in circulation, offering a natural lens on a longstanding longevity gap.

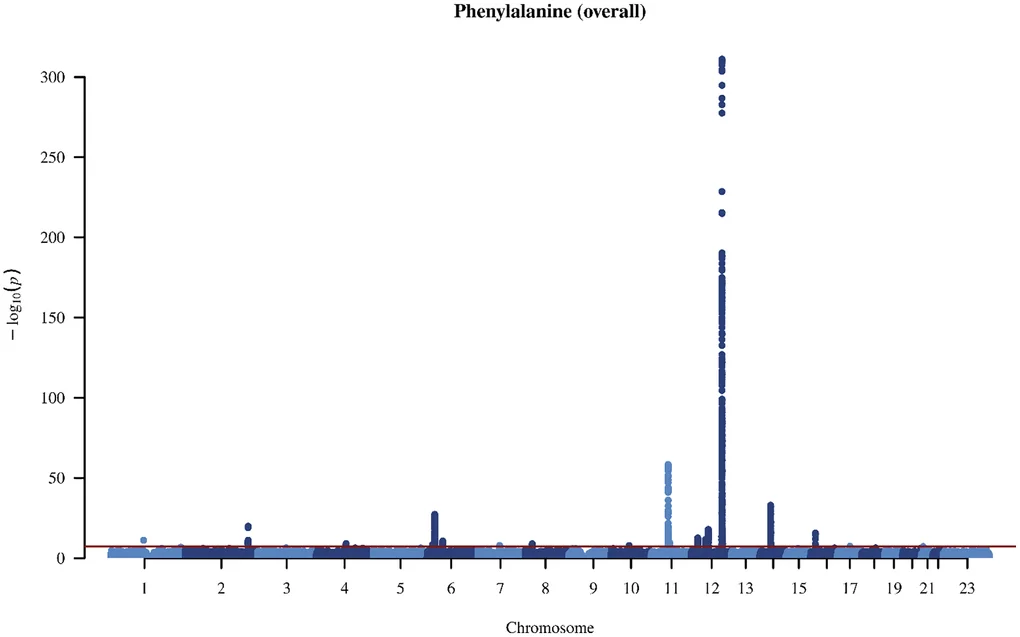

In a new study published in Aging (Albany NY) in 2025 (DOI: 10.18632/aging.206326), researchers from the University of Hong Kong and the University of Georgia asked a focused question: do circulating levels of tyrosine and phenylalanine track with lifespan, and do those links differ for men and women? To cut through confounding that can muddy observational studies, they paired a large UK Biobank cohort analysis with Mendelian randomization, which uses genetic variants as instruments to test causality.

Inside the UK Biobank: what the data show

The team analyzed 272,475 adults in the UK Biobank with blood measurements of amino acids and detailed health and lifestyle data. Over a median follow-up of about 11 years, 23,964 deaths occurred. After adjusting for age, socioeconomic measures, smoking, alcohol use, physical activity, ethnicity, education, and body mass index, higher phenylalanine tracked with a higher risk of all-cause mortality (hazard ratio 1.04 per standard deviation increase; 95% CI 1.03–1.05). Tyrosine showed a smaller but notable signal overall and in men (HR 1.03; 95% CI 1.01–1.05), but not in women (HR 1.00; 95% CI 0.98–1.03).

The relationship was not strictly linear. Spline analyses suggested a turning point around average concentrations, hinting that risk may rise chiefly at the higher end of the distribution—an important nuance for clinical interpretation. The two amino acids correlated moderately (r = 0.52), and their ratio told a subtler story: a higher tyrosine-to-phenylalanine ratio associated with lower mortality risk in women, but not in men.

When the researchers drilled into cause-specific mortality, phenylalanine stood out again, associating positively with cardiovascular and cancer deaths. Tyrosine did not show clear disease-specific associations in these observational data, underscoring the importance of testing whether tyrosine itself exerts an independent effect on longevity.

Testing causality with genetics

Observational associations can be distorted by hidden confounders. To probe causality, the team used Mendelian randomization (MR), selecting independent genetic variants strongly linked to circulating tyrosine and phenylalanine and then estimating their effects on parental lifespan across nearly 400,000 UK Biobank participants. MR can approximate a randomized experiment because genetic variants are assigned at conception and are less tangled with lifestyle and socioeconomic factors.

Across multiple MR methods, genetically higher tyrosine levels associated with shorter lifespan in the combined sample and in men, with consistent directions in sensitivity analyses. In a multivariable MR that considered tyrosine and phenylalanine together, the tyrosine signal remained robust in men: each standard deviation higher genetically predicted tyrosine corresponded to 0.91 fewer years of life (95% CI −1.60 to −0.21). The association was not evident in women. Phenylalanine, meanwhile, did not show an independent relationship with lifespan after accounting for tyrosine.

“Reducing tyrosine in people with elevated concentrations may contribute to prolonging lifespan, with potential sex-specific differences,” write Jie V. Zhao and colleagues. “It is worthwhile to explore pathways underlying the sex-specific effects.”

That sex split is tantalizing rather than definitive: while directions were consistent, formal tests for sex differences did not always reach statistical significance, and power to detect modest interactions was limited. Still, the convergence of observational and genetic evidence points to tyrosine as the more likely driver of the longevity link.

Why the signal may differ in men and women

Biology provides several plausible threads. Tyrosine feeds catecholamine neurotransmitters that shape mood, cognition, and stress responses—systems modulated by sex hormones. It also tracks with insulin resistance in epidemiologic studies, a state that nudges metabolism toward growth and reproduction at the expense of repair, a classic trade-off in evolutionary biology. Testosterone and estrogen interact with both dopamine circuits and insulin pathways, raising the possibility that the same tyrosine level could have different downstream effects in male and female physiology.

“From the perspective of etiology, our study suggests that tyrosine is involved in longevity,” the authors note.

Animal work offers complementary hints. In models ranging from flies to rodents, protein restriction can extend lifespan while lowering tissue tyrosine levels and dialing down mTORC1 and IIS signaling—nutrient-sensing pathways intimately tied to aging. The new human data do not prove that cutting dietary tyrosine lengthens life, but they align with a picture in which higher circulating tyrosine may, under some conditions, tilt biology toward shorter survival.

What this means for diets and supplements

The immediate message is not to fear foods containing tyrosine or phenylalanine. The study measured circulating levels at a single baseline time point and used genetics to model lifelong exposure; it did not test a diet or a supplement. Blood amino acids reflect a tapestry of diet, metabolism, tissue uptake, and clearance, and the observed nonlinearity suggests that potential risk may concentrate among people with elevated levels.

That said, the findings raise eyebrows for one increasingly popular product category: tyrosine supplements marketed for focus and mood. The authors are careful, but clear.

“Tyrosine is also a popular nutrient supplement, promoted as a neurotransmitter support for a positive mood and mental alertness. Our study is not directly related to tyrosine supplement, but given tyrosine supplement may increase blood tyrosine, our study did not support the benefit of long-term use of tyrosine on lifespan.”

For public health, the more actionable signal may be upstream: patterns of eating that lower circulating tyrosine—such as prudent protein moderation or shifts in protein sources—could someday become part of personalized longevity strategies, particularly for men with high baseline levels. Any such approach will require careful trials to balance potential benefits for aging against cognitive or performance effects tied to catecholamine synthesis.

Caveats and the road ahead

Like all studies, this one has limitations. The observational analysis, despite extensive adjustment, cannot abolish confounding. The MR analysis, while more robust, relies on assumptions about the genetic instruments and included overlapping samples for exposure and outcome—choices the authors probed in sensitivity tests but that merit replication in independent datasets. Both amino acids were measured once, so temporal changes and cumulative exposure are unknown. And because the spline analyses suggest nonlinearity, the headline associations should be interpreted primarily for individuals with higher circulating levels.

Mechanistic work is also needed. Do tyrosine’s links to insulin resistance, stress catecholamines, or immune signaling explain the sex-specific patterns? Can targeted lifestyle changes lower tyrosine sustainably without trade-offs? The answers will shape how clinicians and the public translate these intriguing associations into action.