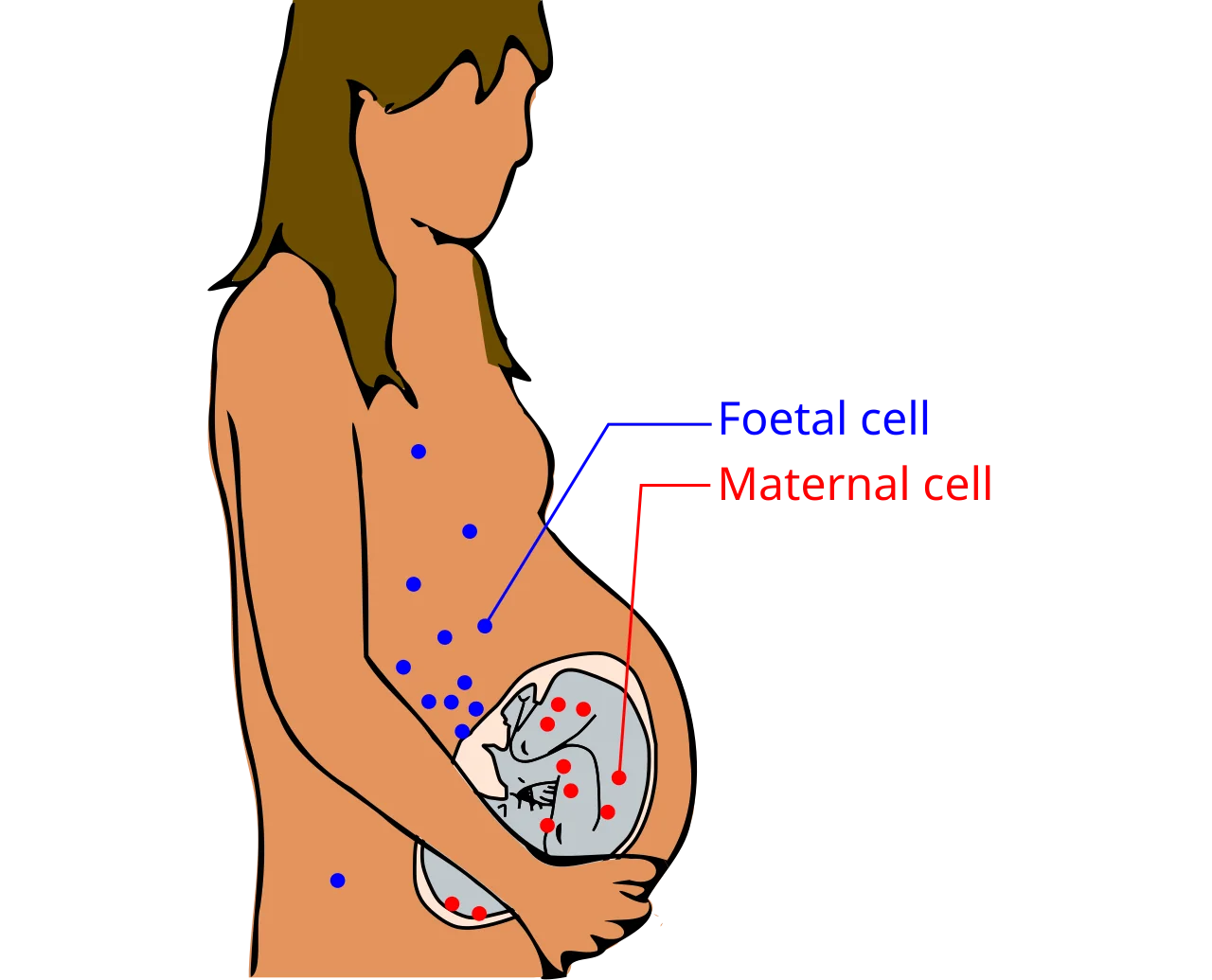

Fetal microchimerism is the presence of a small number of fetal cells that enter a mother’s body during pregnancy and persist for years or even decades. It happens when some fetal cells cross the placenta into the maternal bloodstream, settle in organs, and sometimes integrate into tissues. These cells may contribute to tissue repair in certain contexts, but they have also been associated with some autoimmune conditions, so their effects appear mixed.

Definition: Fetal microchimerism is the long-term persistence of a tiny population of fetal-origin cells in a mother after pregnancy.

What is fetal microchimerism?

Microchimerism means an individual carries a very small number of genetically distinct cells from another individual. In pregnancy, bidirectional cell exchange can occur, but the most studied form is fetal cells in the mother. Researchers first detected these cells by looking for Y-chromosome DNA in women who had carried sons, then expanded to other genetic markers and cell types in comprehensive reviews.

Studies have identified fetal-origin cells in maternal blood, thyroid, skin, liver, lung, kidney, heart, and even brain many years after childbirth (evidence in brain tissue).

How does fetal microchimerism work?

Late in the first trimester and increasingly as pregnancy progresses, small numbers of fetal cells cross the placental barrier into maternal circulation. This process is part of normal maternal-fetal cell trafficking. The fetal cells include immune cells, hematopoietic progenitors, and mesenchymal stem-like cells. After entering the mother’s blood, some are cleared, while others home to sites of injury or inflammation, take up residence, and can persist long term (review).

Because some of these trafficked cells have progenitor or stem-like properties, they may differentiate into tissue-specific cells, such as epithelial cells in skin or hepatocytes in the liver. Animal studies and human case series suggest these fetal cells are more likely to be found, and sometimes to expand, at maternal injury sites, which hints at a role in repair and remodeling (review).

Where are fetal microchimeric cells found in the body?

Detection methods vary, but fetal-origin cells and DNA have been reported in:

- Blood, often transiently at higher levels near delivery, with lower but detectable levels years later.

- Thyroid and skin, where they may participate in local immune responses and wound healing.

- Liver, lung, and kidney, typically as rare cells identifiable by fetal-specific genetic markers.

- Heart, especially after maternal cardiac injury in animal models, where fetal cells have been observed at damage sites.

- Brain, as male microchimerism has been identified in women who previously carried sons (PLoS ONE study).

Is fetal microchimerism beneficial or harmful?

Evidence suggests both potential benefits and risks, depending on context.

Potential benefits

- Tissue repair: Fetal cells are enriched at maternal injury or inflammation sites in animal studies and some human observations, and may differentiate into local cell types involved in healing (review).

- Immune surveillance: Some research proposes these cells might contribute to anti-tumor responses or be associated with lower risk of certain cancers in some populations, though findings vary across studies (review).

Potential risks

- Autoimmune disease: Women with conditions such as systemic sclerosis, autoimmune thyroid disease, or lupus can show differences in microchimeric cell levels or localization compared to controls in some studies. Whether fetal microchimerism contributes to disease or is a byproduct of inflammation remains under debate (review).

- Allergic and inflammatory responses: Hypotheses link microchimerism to altered immune reactivity postpartum, but clear causal evidence for new-onset allergies is limited.

Overall, fetal microchimerism appears to be a normal outcome of pregnancy with context-dependent effects. Most mothers with microchimeric cells are healthy. Associations with disease are not proof of causation and may reflect underlying immune or tissue environments.

What are the limitations of current research?

- Detection challenges: Microchimeric cells are rare, so studies rely on sensitive DNA assays or cell sorting, which can vary in accuracy and sensitivity.

- Study design: Many findings come from small cohorts, case-control designs, or animal models, which limit causal conclusions.

- Heterogeneity: Different pregnancies, fetal cell types, maternal genetics, and timing since delivery likely influence outcomes, making results hard to generalize.

- Confounding factors: Inflammation and injury both attract microchimeric cells and are features of disease, complicating cause-effect interpretation.

What does this mean for maternal health?

For most people, fetal microchimerism is a silent biological footprint of pregnancy. Its presence alone is not a medical problem. The most practical implications today are in research: scientists are using microchimeric cells to learn about immune tolerance in pregnancy, mechanisms of tissue repair, and the origins of some autoimmune disease associations. There is no validated clinical test or therapy that uses microchimeric cells in routine care, and speculative applications, such as anti-aging treatments, are not supported by clinical evidence.

If you have postpartum health changes or autoimmune symptoms, talk with a clinician. While microchimerism is an active research area, established evaluation and treatment still rely on standard diagnostic and therapeutic pathways.